Cape Bruny Lighthouse History

When first lit in March 1838, the Cape Bruny Lighthouse was Tasmania’s third lighthouse, after the Iron Pot Lighthouse at the entrance to the River Derwent and the Low Head Lighthouse at the entrance to the River Tamar. It was Australia’s fourth lighthouse. It is now the country’s second oldest and longest continually staffed extant lighthouse.

The Cape Bruny Lighthouse project was commissioned by Governor George Arthur in 1835 after a series of tragic shipwrecks south of Bruny Island, Tasmania.

John Lee Archer submitted his final design for Bruny Island Lighthouse in January 1836. Construction began April 1836 but it took longer than Archer forecast. Partly due to the fact that the person he proposed be put in charge to oversee the building works, Charles Watson, was not approved by Arthur because he was originally a convict.

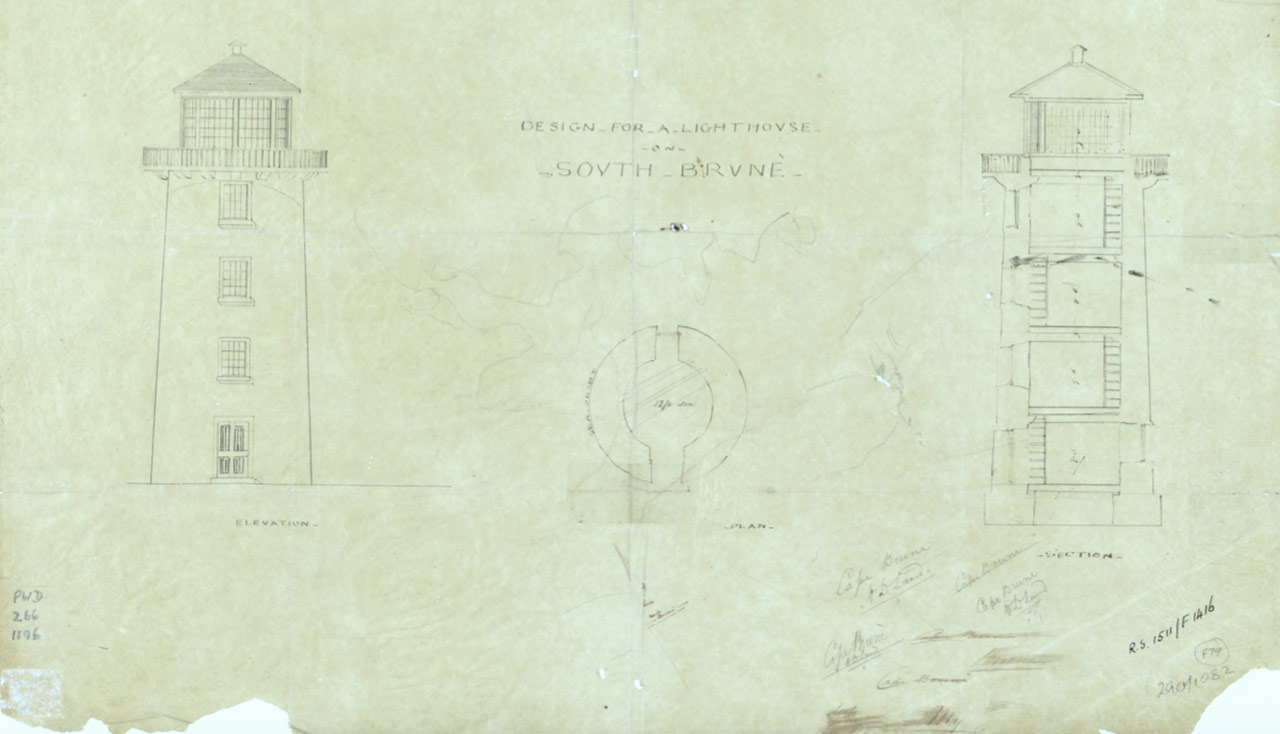

John Lee Archers drawings of Cape Bruny Lighthouse 1835… showing the internal wooden steps and landings that were removed in 1902/3. Also showing the original lantern room also replaced in 1902/3

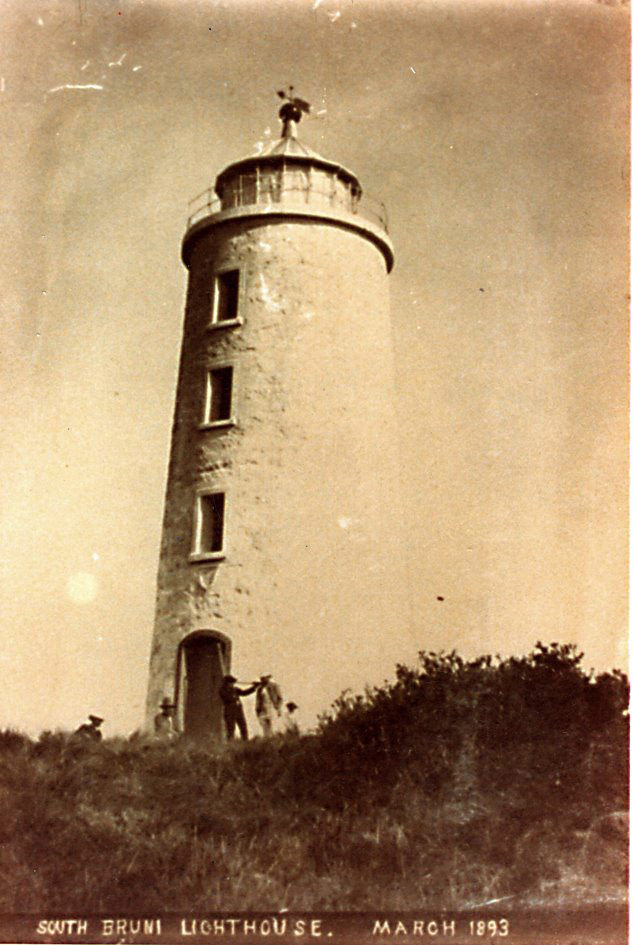

Watson received a condition pardon in 1834 and in 1836 he was sent to South Bruny to supervise the building of Australia’s third lighthouse with his team of 12 convicts. It was constructed from locally quarried dolerite and Bruny Island lighthouse was completed and first lit in March 1838.

John Lee Archer was very proud of his lighthouses. Four months prior to Cape Bruny being completed, in November 1837, he took his wife Sophia and three-year old daughter Charlotte to see the Iron Pot Bay and Bruny Island Lighthouses. They spent 9 days visiting Iron Pot, Cygnet, Port Esperance, Recherche Bay and Bruny Island.

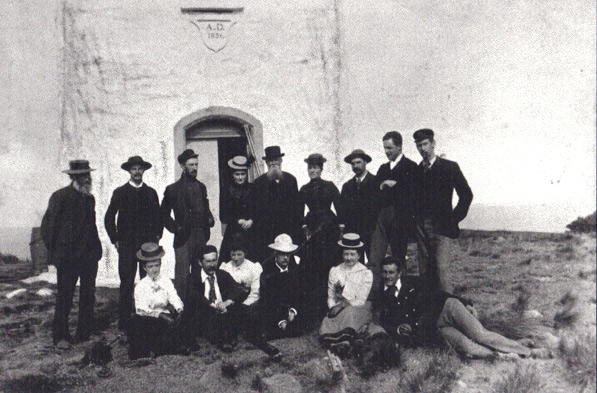

Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

Lighthouses, so often located in wild and spectacular places redolent of storms, remote landscapes and shipwrecks, evoke strong emotions in most of us. The Cape Bruny Lighthouse on its rugged cliff top is no different.

The story of lighthouses invariably begins with shipwrecks. Cape Bruny and our southern coastlines were feared by many early navigators and Tasmania has over 400 shipwrecks around its wild coastlines. The catastrophic wreck of the convict transport ship George III, with the loss of 134 lives in April 1835 and the earlier wreck of the Actaeon (wrecked on what’s now known as the Actean Reef) south of Bruny Island in 1822, prompted Governor George Arthur to erect a lighthouse to guide the vessels past at Cape Bruny.

A lighthouse reserve of 74.5 hectares (184 acres), provided timber, vegetable gardens and grazing land, all indispensable parts of its operation. Cape Bruny’s first superintendent, William Baudinet, was assisted by three convicts in operating the station. Convicts staffed most of Tasmania’s lighthouses until 1855. Baudinet himself, as was common on Tasmania’s nineteenth century lights, founded a family of lightkeepers with several descendants serving on various Tasmanian light stations.

Life for Cape Bruny’s nineteenth century lightkeepers was sublime in its spectacular isolation, demanding in the physical work required and mundane in its day to day duties. Despite their long hours on duty, Tasmanian lightkeepers were poorly paid and many toiled for years without leave. After 1878 staff at Cape Bruny enjoyed 14 days leave per annum with half their passage to and from the island paid. While duties such as chopping firewood, unloading stores or repairing roads might be postponed on special occasions, keeping the brasswork and lamps polished, the windows cleaned, spare lamps in order and the light illuminated at night was a daily task.

Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

The nightly task of maintaining the light was unremitting for the Cape Bruny Lighthouse keepers through the 19th and early 20th centuries. Each lighthouse had a unique light characteristic which was ensured by a clockwork planetary table requiring rewinding every eight hours but rewound about every hour routinely to help the keepers stay awake. The fifteen lamps of the original 1838 Wilkins lantern each burned 600mls of expensive sperm whale oil per hour and needed frequent refilling. The lamps were extremely fragile, being replaced every three nights in 1839. Light keepers who neglected these primary duties of maintaining the light risked summary dismissal — the Marine Board’s lighthouse inspector, James Meech, boasted that ‘he made Lighthouse Keepers tremble’ during inspections.

Initially, contact with Hobart for the keepers of the light at Cape Bruny, was either by sea or via a long rough track to North Bruny Island. Supplies were shipped to a jetty five kilometres away at Great Taylors Bay from at least the 1850s.

Old Jetty Beach Horse and Cart 1893. Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

Old Jetty Beach Horse and Cart 1893. Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

In emergencies, lighthouse staff signalled passing ships or made time consuming and hazardous journeys up the island or across the D’Entrecasteaux Channel to obtain assistance. Communications improved when the first telephone line reached the light station in 1902.

Superintendents usually had a seafaring background and needed to be capable and resourceful men, “A Jack of all trades”.

They kept log books and reports of weather observations and passing sea traffic for the Marine Board. Assistant keepers mostly attended to night watches of the light and were directed by the Head Keeper.

There have been three known deaths around the Cape Bruny lighthouse.

Assistant keeper Isaac Merrick’s two year old daughter Christina choked on a piece of turnip and died in 1875.

Her grave can be found today overlooking the beach next to the grave of lighthouse keeper A. Williams’ child who died of infant diarrhoea in 1898.

Cape Bruny’s third recorded fatality occurred when Rupert Peters fell while descending a cliff, just below the Lighthouse, to go fishing in 1937.

Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

Image donated by the Bruny Island Historical Society

The Cape Bruny Lighthouse and its last keeper, John Cook were made redundant in 1993.

John Cook was a keeper of lights for 25 years and spent 13 years at Cape Bruny.

“I didn’t want to leave, when the time came I was very sad, everything was becoming automated it was like the tide coming in and you couldn’t stop it,” says John, the last and second longest serving keeper at Bruny.

Craig Parsey’s (Managing Director of Bruny Island Safaris and Cape Bruny Lighthouse Tours) family, Anthony & Robyn Parsey, were Lighthouse Keepers with John Cook on Maatsuyker Island off the South Coast of Tasmania, Australia’s Southernmost Lighthouse, later being transferred to Eddystone Point in the North East of Tasmania, Low Head on the Tamar River and finally to Cape Bruny where Craig attended his first school. Previous to this he was home schooled at each light station. Many of the stories you will hear about being at the Cape Bruny Lighthouse Station are derived from real life experiences of Craig’s family and from many interviews with John Cook. John & Chris Denmen and family also deserve a special mention and were a big part of the lives of the Parsey Lighthouse Keeper family, spending many years on Maatsuyker and Eddystone Point until closure. John Cook, John Denmen and Tony Parsey are amongst the last kerosene keepers in Australia.

Images below are provided by Anthony Parsey – Former Lightkeeper

Cape Bruny Lighthouse Tours is managed and operated by Bruny Island Safaris